On April 8, 2021, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper signed Executive Order 208, establishing the Juvenile Sentence Review Board. This board is a new mechanism for executive clemency, which has been described as “provid[ing] the ‘fail-safe’ in our criminal justice system.”[1] Often serving as the last resort for someone convicted of a crime, clemency allows for a change in a person’s conviction or sentence, usually many years after the conviction and sentence became final. More than that, clemency is, in the words of former North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford, an “important attitude of a healthy society—that of mercy beyond the strict framework of the law.[2]” Unfortunately, as described below, mercy has disappeared from the executive branch in North Carolina, as there have been no sentence commutations or pardons of forgiveness granted since 2002. We hope the Juvenile Sentence Review Board will serve to revive this important but neglected area of executive power in our state.

“The Governor may grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons, after conviction, for all offenses (except in cases of impeachment), upon such conditions as he may think proper, subject to regulations prescribed by law relative to the manner of applying for pardons. The terms reprieves, commutations, and pardons shall not include paroles.”

With this statement in Article III, § 5(6), the drafters of the 1971 North Carolina Constitution gave the right to grant clemency from a criminal conviction to the Governor. This was not a new concept. English monarchs had the power, as has every Tar Heel governor since the first state constitution in 1776.[3]

The North Carolina General Assembly has very limited authority in the clemency process, as the 1971 Constitution limits the Assembly’s power to providing the manner of applying for a pardon. Given the bare-bones nature of guidance from both the executive and legislative branches, we will attempt to answer the following questions using what is officially and unofficially known about the process in North Carolina:

We will then abandon the attempt at official answers to address two additional questions:

Officially: Executive clemency in North Carolina takes the form of a commutation or a pardon. Commutation means changing the sentence that someone is presently serving. This can take the form of reducing the sentence by a certain amount or changing the nature of the sentence. One historical use of the commutation power was to remove someone from death row. The person’s capital sentence was changed to life with or without the possibility of parole.[4]

Pardons take on three forms in North Carolina: forgiveness, unconditional, or innocence. These pardons are merely official statements “attached to the criminal record that states that the State of North Carolina has pardoned the crime.”[5]While a pardon of forgiveness is granted with certain conditions, an unconditional pardon—as the name implies—does not.[6] The unconditional pardon was traditionally granted “primarily to restore an individual’s right to own or possess a firearm.”[7] However, the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled in 2013 that a pardon of forgiveness removes the ban in N.C. Gen. Stat. § 14-415.1 on possession of a firearm by a person convicted of a felony.[8] Therefore, the unconditional pardon may now be redundant.

None of these pardons erases the record of a person’s conviction. “Under the North Carolina Constitution, the Executive Branch does not have the authority to expunge a criminal record.”[9] Instead, petitioners must follow the statutory requirements for expungement.[10] However, a pardon of innocence authorizes an expunction.[11] In addition, while a conviction that has been pardoned cannot be used in later proceedings,[12] only pardons of innocence remove the collateral consequences associated with a conviction.[13] Finally, a pardon of innocence is required before an individual can seek compensation from the state for wrongful incarceration.[14]

Unofficially: The Governor has authority to makes any change to a sentence, other than make it longer. But the Governor alone can’t compensate someone wrongly convicted or make sure that a successful clemency petitioner’s record is clean.

Additionally, much of the official guidance on clemency comes from the Governor’s Clemency Office’s website, but information on the website is outdated and does not appear to have been updated since Gov. Cooper took office.[15] Thus, the information available may not reflect current policies.

Officially: Commutations, by their nature, cannot be granted until after conviction. North Carolina law holds that the same is true for pardons.[16]

Neither the North Carolina Constitution nor the North Carolina General Statutes place limits on the Governor’s commutation powers.[17] The Governor’s Clemency Office has determined that pardons of forgiveness and unconditional pardons “[m]ay be granted to those individuals who have maintained a good reputation in their community, following the completion of their sentence for a criminal offense.” It must have been more than 5 years since the petitioner was “released from State supervision” (including prison, probation, or parole).[18]

A pardon of innocence, unsurprisingly, is different. This pardon is “granted when an individual has been convicted and the criminal charges are subsequently dismissed.”[19]

Unofficially official: The Governor’s Clemency Office has rules about who will and won’t be considered for clemency. However, those rules are not published anywhere. People in prison and advocates for clemency are not informed of these rules. In addition, these rules can change at any time as the governor sees fit. Below are the rules reportedly imposed by Gov. Cooper.

One stands out. People eligible for parole are ineligible for clemency. An informal poll of clemency advocates in North Carolina revealed that not one person was aware of this restriction until recently, though Gov. Cooper has been in office for over 4 years.

The other rules:[20]

Unofficially: Anyone who has been convicted of a crime and has a good record since then can receive clemency.

Officially: Clemency petitions must be made in writing to the Governor.

Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 147-21, applications for a pardon must:

The General Assembly is limited by the NC Constitution to providing for the manner of applying for a pardon only, so no statute or published requirements exist for commutation and reprieve applications.

Unofficially: Write to the Governor and ask. The clemency process takes place outside the courtroom and usually many years after the person was convicted and sentenced. Therefore, a person may seek clemency for a variety of reasons that may not have been part of prior adjudications. Clemency petitions are not governed by the same rules and requirements that govern court proceedings.

Officially: The Governor has the sole and exclusive right to decide clemency petitions.[21] “State clemency procedures generally comport with due process when a prisoner is afforded notice and the opportunity to participate in clemency procedures, and the clemency decision, though substantively a discretionary one, is not reached by means of a procedure such as a coin toss.”[22]

While the Governor is the decisionmaker, two groups assist him in his duties. First, the Governor's Clemency Office processes all clemency petitions. “It oversees, coordinates, prepares reports and drafts Executive Clemency Orders for the Governor. This office also acts as the liaison with federal, state, and county officials and other parties interested in clemency.”[23] In addition, the North Carolina Post Release Supervision and Parole Commission has the authority “to assist the Governor in exercising his authority in granting reprieves, commutations, and pardons, and shall perform such other services as may be required by the Governor in exercising his powers of executive clemency.”[24]

Unofficially: We have no idea.

Officially: The Governor is required to keep a “register of all applications for pardon, or for commutation of any sentence, with a list of the official signatures and recommendations in favor of such application.”[25] No other information about clemency petitions is required to be made public, as clemency petitions do not fall within North Carolina’s public records laws.[26]

Under new victims’ rights amendments to the N.C. Constitution made in 2018, the Governor's Clemency Office shall notify a victim:

Unofficially: Virtually none. Gov. Cooper has taken the position that all clemency information falls outside of North Carolina’s public records law, and he is the first Governor in recent memory to refuse to make public the list of clemency applications received.[28]

Officially: Yes, if the person violates the conditions placed upon him/her when clemency is granted. Under N.C. Gen. Stat. § 147-24, the Governor must arrest anyone who violates their pardon conditions when the Governor “receiv[es] information of such violations.” The Governor must then decide whether the person really did violate the conditions imposed.

The standard for making this determination is “by such evidence as the Governor may require.” If the Governor is satisfied that the person has violated, the Governor must send the person back to prison to serve whatever amount of the original sentence remains.[29] If the Governor does not believe the person violated his/her conditions, the person “shall be released” and the conditional pardon “shall remain in force.”

Unofficially: N.C. Gen. Stat. § 147-24 has no practical application. A commutation is different from a pardon under the NC Constitution, and a person will only have a sentence to serve if that person receives a sentence reduction (commutation) subject to conditions. A pardon is only available 5 years after “release from State supervision.”[30] As a result, no person can be incarcerated subject to the provisions of § 147-24. A person may violate conditions set at the time of a commutation and, presumably, the Governor would have the authority to order the person back to prison if the commutation resulted in early release.[31]

Officially: Some people. You can search Google for “pardon” and the name of your favorite North Carolina Governor if you want names.

Unofficially: Nobody these days.

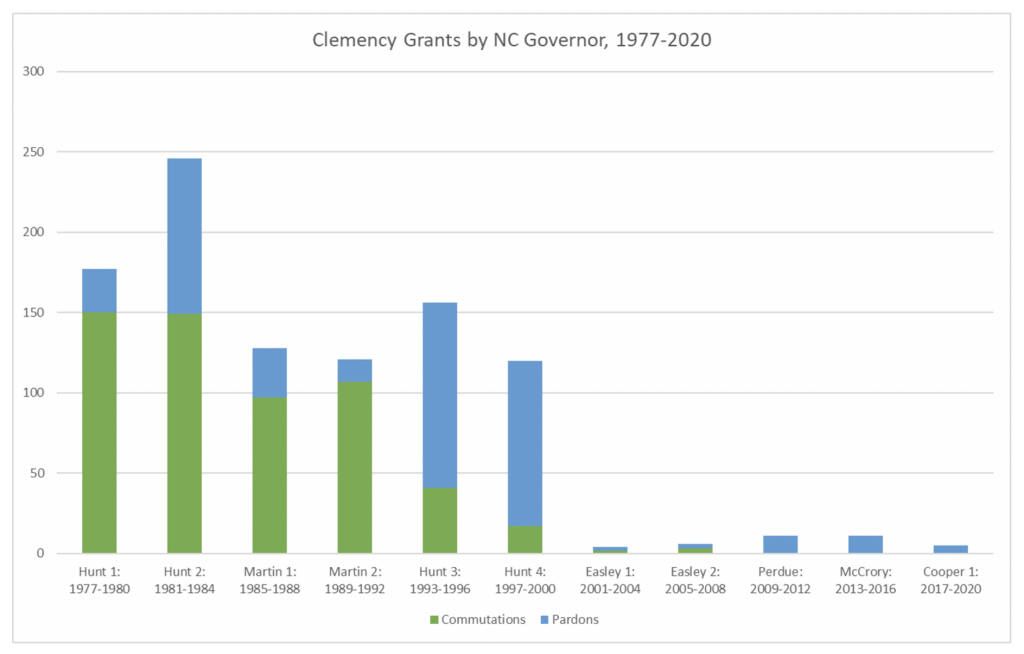

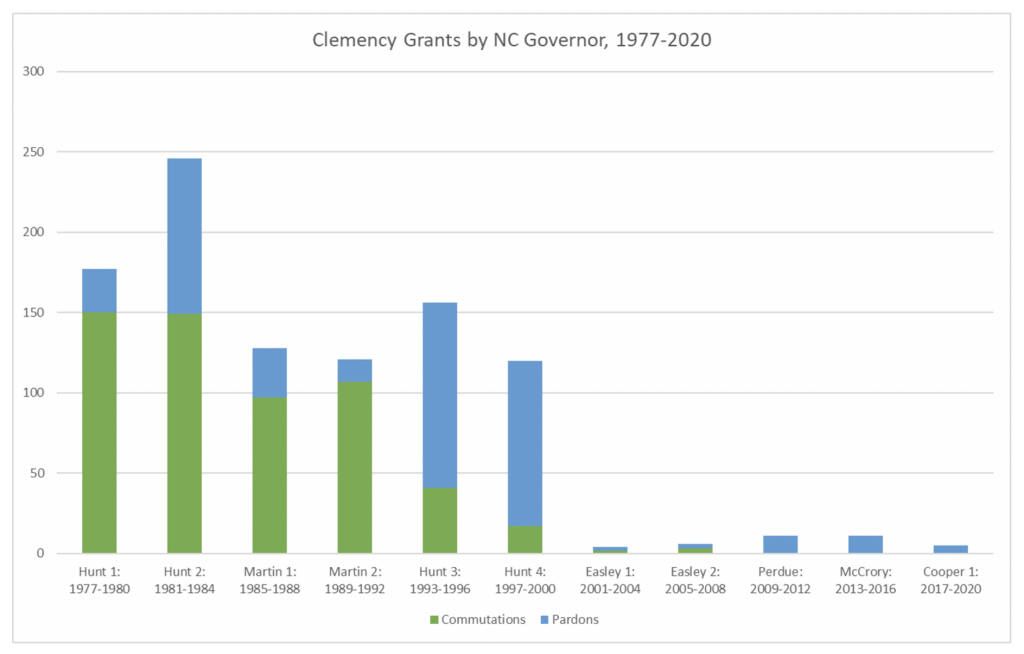

As you can see from this chart, the use of executive clemency dropped off a cliff after the year 2000. The use of commutations decreased greatly after 1992. Why?

First, during the Presidential campaign in 1988, George H.W. Bush repeatedly painted Michael Dukakis as “soft on crime.” Prior to Dukakis becoming the governor, Massachusetts instituted a program that allowed people in prison to earn weekend passes. One of the people using weekend passes was Willie Horton, who had been convicted of murder, and he subsequently raped a Maryland woman during such a furlough. An organization supporting Bush ran an ad assailing Dukakis for “allowing” Horton to be released. Bush’s official campaign did not object to the ad until it had run for 25 of its scheduled 28 days. [32]

The ad was discussed repeatedly during nightly newscasts. In the short term, it contributed to Dukakis’s loss to Bush. In the long term, it forced Democrats to campaign as “tough on crime” and seek “truth in sentencing.”[33]

At the state level, North Carolina’s move toward more sentencing “truth” began with the establishment of the Sentencing and Policy Advisory Commission in 1990. After considerable study, the Commission’s recommendation led to the passage of the Structured Sentencing Act in 1994.[34] Under Structured Sentencing, parole was eliminated, among other changes.

As the Sentencing Commission was making recommendations, Bill Clinton was promising to “take back” neighborhoods and restore “order and safety” during his first term as President.[35] The result was the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which was intended to increase incarceration.[36]

Therefore, when Jim Hunt successfully won North Carolina’s gubernatorial election for the third time, he was confronted with a much different climate on crime than during his first two terms.[37] It appears that he simply could not bring himself to commute the same number of sentences he had during the late 1970s and early 1980s. While he still issued a large number of pardons, these may have simply been pardons of forgiveness, which are the type “most frequently requested.”[38]

Emblematic of this shift is the change in commutation of capital sentences. Between 1977, when Hunt first became Governor, and 1989, 26 people were removed from death row by executive clemency.[39] The number of death sentences in North Carolina then peaked in 1994.[40] Despite the increased number of people eligible for clemency, not a single death sentence has been commuted since 2002.[41]

Second, Hunt was then followed as Governor by former District Attorney and Attorney General Michael Easley. Easley appears to have simply had no interest in either commutation or pardon.

Where clemency had once been a routine part of each Governor’s term, Easley reduced it to an afterthought reserved for the obviously innocent. The three governors who have followed Easley have retained his distaste for clemency. Every single grant of clemency since Easley left office has been a pardon of innocence.[42] Clemency in North Carolina has become a political football.

For those who have been following the unofficial answers closely, you have noticed that the current state of affairs is bleak. Practitioners in North Carolina know that Gov. Cooper can do, essentially, whatever he wants when it comes to clemency. However, there is little information available, even about how decisions will be made, and Gov. Cooper has yet to reduce a sentence.

This inaction is particularly frustrating for advocates in light of recent polling that shows broad support for using clemency to reduce the prison population. Overall, 72% of those surveyed support the use of clemency power to shorten the sentences of people the Governor believes are serving excessive sentences and do not pose a threat to public safety. This support extends to the use of clemency in several specific situations, with the percentage approving noted:

Based on the above, lots of people. First, despite continued attempts to increase “truth” in sentencing, there is clear racial bias in North Carolina prison terms.[44]

Black/African-American people make up:

People of color make up:

Second, as of January, there were 939 people in NC prisons who would not be incarcerated under current law, were eligible for parole, and were not in restrictive custody (meaning they had not been found guilty of recent violent infractions). In particular, there were 44 people still incarcerated for non-homicide, non-sex crimes committed prior to October 1, 1994, who had good incarceration records. These 44 people have served more than 26 years for crimes that carry maximum punishments of 15 years today.

Third, as of June 30, 2021, there will be 7,198 people over the age of 50 in NC prisons. While this is a large number, “for at least the next 20 years we can expect that the number of older individuals in the system will continue to rise, and dramatically so.”[46]

Fourth, as of June 5, 2021, there were 1,019 people in prison for crimes they committed as juveniles. Fifth, as of November 2020, there were 8,517 people in NC prisons who had served more than 20 years. And finally, as of January 2021, there were 3,734 people in NC prisons on drug crimes.

In other words, there are thousands of people that the public would support releasing from prison, even without considering that doing so would address the horrific racial disparities produced by the North Carolina sentencing scheme.

On April 8, 2021, Gov. Cooper announced the formation of a new clemency group: the Juvenile Sentence Review Board (JSRB).[47] The JSRB is intended to serve as an advisory board to “[r]eview sentences imposed on juveniles in North Carolina and make recommendations concerning clemency and commutation of such sentences when appropriate.” The Board’s mandate is to “promote sentencing outcomes that consider the fundamental differences between juveniles and adults and address the structural impact of racial bias while maintaining public safety.”

The JSRB is a response not just to the terrible racial disparities demonstrated above, but also to North Carolina’s historical place as an outlier among states in its treatment of minors accused of crimes. Until December 1, 2019, every 16-year-old accused of a crime in North Carolina was automatically prosecuted in adult court. As a result, thousands of minors were tried and convicted in criminal courts and sentenced to adult prisons.

This practice persisted despite a sea change in thinking about the significance of youth in criminal culpability. Drawing on neuroscience and developmental psychology, the United States Supreme Court in 2005 began to restructure the constitutional limitations on sentencing of juveniles. In three landmark cases—Roper v. Simmons, Graham v. Florida, and Miller v. Alabama—the court held that “children are constitutionally different from adults for sentencing purposes.”[48]Therefore, the Court found that the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit capital sentences, life without parole (LWOP) sentences for non-homicides, and mandatory LWOP for individuals who commit crimes while under the age of eighteen.

These holdings were based on three important findings from studies of adolescents. Neurologists and developmental psychologists found that children have:

The JSRB will begin reviewing petitions this fall. The group of eligible people will have served at least 15 years for crimes committed when they were children. The JSRB is also to consider the following criteria for eligible individuals:

The Juvenile Sentence Review Board is the first attempt by the Cooper administration to address the thousands of people that the public would support releasing from prison and the racial imbalances in sentencing. Of those eligible for JSRB review, 74.6% are Black/African-American, while only 17.6% are White. Based on the 2010 Census and recent prison data, Black/African-American boys make up:

Meanwhile, children of color make up:

Note that the round figures of 80% and 90% of children receiving terms of more than 60 years comes from the fact that this has only happened 10 times in NC history. (This does not include sentences of life.) Of those 10 extreme sentences for children, 8 have been handed out to black boys, though they are only 13% of our state. Only once has such a harsh sentence been given to a White child.

One reason why so many children remain in prison for so many years is that they accumulate slightly more infractions than people who go in as adults. There are two reasons for this difference. First, as noted above, children are more impulsive and less able to regulate their emotions than adults. This leads to acting out, especially by children forced into harsh prison environments.

Second, infractions in North Carolina prisons are also handed out in a racially discriminatory fashion:

| Race/ Ethnicity | % of NC pop. | % of prison pop. | % of infractions |

| Am. In./Nat. Am./Indg. | 1.6 | 2.1 | 2.7 |

| Asian/As-Am. | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Black/Af-Am. | 21.5 | 50.8 | 65.0 |

| Latinx | 9.8 | 5.5 | 3.5 |

| Two or more | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| White | 62.6 | 39.6 | 27.6 |

As you can see, Black/African-American people should receive about 50.8% of the infractions in prison. Instead, they receive 65%, which is just over 14% more. White people in prison, meanwhile, receive 12% fewer infractions than would be statistically expected.

Again, the work of the Juvenile Sentence Review Board is an important first step to redress the harsh, racially imbalanced sentences handed out in our state to children of color, particularly Black/African-American boys. Gov. Cooper appointed four experienced attorneys to take on this task.[50]

Finally, we conclude by returning to the words of former North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford, who said, “I fully realize that reasonable men hold strong feelings on both sides of every case where executive clemency is indicated. I accepted the responsibility of being Governor, however, and I will not shy away from the responsibility of exercising the power of executive clemency.[51]”

Governors in North Carolina have shied away from clemency for nearly 20 years, and we look forward to Gov. Cooper once again accepting the responsibility to extend mercy on behalf of the State by working closely with the Juvenile Sentence Review Board to commute the sentences of deserving individuals.

References: